https://feedly.com/i/entry/ty+AzTYZ3TUuMuPycOdkUNamwQCXNpDbajbdLnbrc5c=_16f176f7813:1f7c171:69b9f616

https://feedly.com/i/entry/ty+AzTYZ3TUuMuPycOdkUNamwQCXNpDbajbdLnbrc5c=_16f176f7813:1f7c171:69b9f616

Visualizzazione post con etichetta john leslie end of the world. Mostra tutti i post

Visualizzazione post con etichetta john leslie end of the world. Mostra tutti i post

mercoledì 18 dicembre 2019

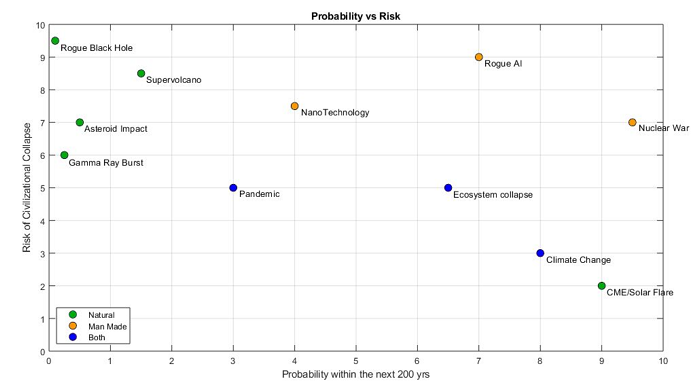

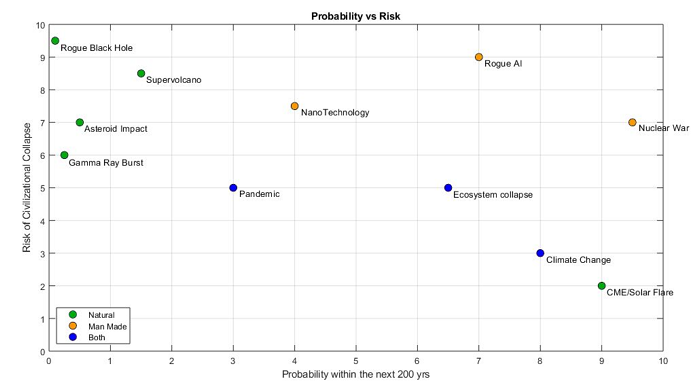

TABELLA DEL RISCHIO ESISTENZIALE

https://feedly.com/i/entry/ty+AzTYZ3TUuMuPycOdkUNamwQCXNpDbajbdLnbrc5c=_16f176f7813:1f7c171:69b9f616

https://feedly.com/i/entry/ty+AzTYZ3TUuMuPycOdkUNamwQCXNpDbajbdLnbrc5c=_16f176f7813:1f7c171:69b9f616

sabato 11 febbraio 2017

La fine del mondo

La razza umana si estinguerà presto?

Secondo John Leslie (The End of the World: The Science and Ethics of Human Extinction), a questa domanda si risponde per gradi e mai in modo certo. Il cosmologo e matematico Ben Carter ha proposto il primo grado, ovvero l'idea iniziale che la persona ragionevole deve farsi quando ignora tutto o quasi tutto. Il suo argomento è noto come Argomento dell' Apocalisse (AA).

AA è un argomento probabilistico. Un' analogia ce lo fa intuire.

Supponete che un Benefattore decida di elargire un dono a cento beneficiati tra cui ci siete anche voi. Li disporrà casualmente in fila indiana impegnandosi a dare un euro al primo, due euro al secondo e così via fino ad arrivare al centesimo a cui darà cento euro. Quanto riceverete voi? Quanto mettete in conto di ricevere? Che somma apposterete nel vostro budget previsionale? Potreste ricevere solo un euro, ma sarebbe una grande sfiga. Del resto, sarebbe illusorio puntare sui cento euro. La cosa piú ragionevole da fare è pensare a qualcosa a mezza strada. Non riceveremo 50 euro ma, in assenza di indizi, pensare a 50 euro è la cosa più ragionevole.

Supponete adesso che un potente Dio crei un mondo in cui, prima della sua fine, nasceranno 1000 persone. Ogni "uomo" sarà contrassegnato da un cartellino numerato che lo identificherà: il primo nato avrà il cartellino 1, il secondo nato il cartellino 2 e così via fino all'ultimo nato con il cartellino 1000. Anche voi abiterete questo mondo. Domanda: quale sarà il vostro cartellino? E qui ripetiamo quanto detto sopra: sarebbe ben strano che foste tra i primissimi. Così come prima risultava ragionevole appostare nel budget previsionale 50 euro, anche adesso la cosa migliore da fare è sparare nel mucchio: pensare ad un numero intorno al 500 vuol dire sbagliarsi esattamente come dire 1 ma perlomeno l'errore che si fa è molto più equilibrato. In assenza di indicazioni spariamo nel mucchio.

Ebbene, usciamo dalle ipotesi e veniamo alla realtà: questo ragionamento, con qualche variante, si applica anche a noi e al nostro pianeta. Bè, se vale quanto appena detto, se il nostro “cartellino” è un numero a circa mezza strada e se vale ANCHE il grafico qua sotto, allora la fine del mondo è molto più vicina di quel che pensassimo (qualsiasi cosa pensassimo).

***

Attenzione, AA non ci dice nulla su quando l'uomo cesserà di esistere, solo che la cosa accadrà prima del previsto...

... the doomsday argument could do little to tell us how long humankind will survive. What it might indicate, though, is that the likelihood of Doom Soon is greater than we would otherwise think...

In fondo, AP si limita a farci notare quanto poco sia probabile che tu possa collocarti tra i primissimi uomini che hanno abitato la terra...

... Suppose that many thousand intelligent races, all of about the same size, had been more or less bound to evolve in our universe. We couldn’t at all expect to be in the very earliest, could we? Very similarly, it can seem, you and I couldn’t at all expect to find ourselves among the very first of many hundred billion humans—or of the many trillions in a human race which colonized its galaxy. We couldn’t at all expect to be in the first 0.1 per cent, let alone the first 0.001 per cent, of all humans who would ever have observed their positions in time... The doomsday argument aims to show that we ought to feel some reluctance to accept any theory which made us very exceptionally early among all humans who would ever have been born...

AP non serve ad elaborare delle stime probabiliste, quanto a rivederle una volta elaborate.

Dalla minaccia nucleare all'inquinamento, anche il profano sa che la sopravvivenza del nostro mondo non è certa, esistono dei rischi esistenziali. Come interviene AD in una discussione sul rischio esistenziale?...

... even if the ‘total risk’ (obtained by combining the individual risks) appeared to be fairly small, Carter’s doomsday argument could suggest that it should be re-evaluated as large...

***

Facciamo un piccolo elenchino di ciò che mette a rischio l'esistenza dell'umanità.

La guerra nucleare, innanzitutto. La possiamo immaginare scatenata tra grandi potenze, ma anche scatenata da terroristi. Oppure da un riccone che può costruirsi la bomba (i costi si stanno abbassando).

Le guerre biologiche. I terroristi possono agire anche in questo scenario. Ma anche la criminalità: i costi sono bassi e il potenziale distruttivo immenso.

Guerra chimica.

Distruzione dello strato di ozono. Il cancro dilagherebbe. Ma oggi conosciamo meglio il fenomeno e sappiamo come arginarlo.

Effetto serra. Lo conosciamo talmente bene che per molti è l’unico rischio esistenziale.

Avvelenamento da inquinamento. Ho in mente le piogge acide. Centinaia di elementi chimici vengono immessi nell'ambiente e il loro effetto a lungo termine ci è sconosciuto. Chi avrebbe pensato prima che il DDT avrebbe dovuto essere bandito?

Malattie. Nella storia la minaccia più robusta alla nostra esistenza. Chi non ricorda la medievale peste nera? Oggi abbiamo più medicine ma ci muoviamo anche più rapidamente facilitando il contagio.

Eruzioni vulcaniche. Qualcuno le ha viste come una causa di estinzione dei dinosauri: le nubi prodotte dalle eruzioni a catena produrrebbero il cosiddetto "inverno vulcanico".

Asteroidi e comete vaganti. I dinosauri sono spariti per colpa loro, forse. Per tutti noi è più facile perire per colpa loro che vincere la lotteria nazionale. Stima di morte: 1:20000.

Era glaciale dovuta al passaggio di una nube interstellare.

Esplosione di stelle vicine. La vicinanza a supernove ci mette a rischio.

Altre esplosioni cosmiche. Tipo quelle che si producono quando il buco nero completa la sua "evaporazione". O quando due buchi neri si fondono.

Collassi imprevedibili di un sistema complesso. Sono indagati dalla “teoria del caos”: l’aria, il suolo, l’acqua… tutti gli elementi della biosfera interagiscono in modo intricatissimo e nel processo forme di collasso devono essere messe in preventivo.

Altre cause che oggi non conosciamo. Sarebbe assurdo pensare di aver esaurito l’elenco.

Cause naturali a parte, anche il comportamento dell’uomo puo’ determinare la sua estinzione.

Decisione di non avere figli. Difficile ma sempre possibile. In fondo basta escludere relativamente pochi uomini da questa tendenza per consentire alla razza di non estinguersi.

Disastri dall’ingegneria genetica. Potrebbero generarsi degli organismi in grado di riprodursi in modo incontrollato (blob). Oppure organismi in grado di invadere il corpo umano.

Disastri dalle nano-tecnologie. La proliferazione incontrollata di piccoli robot replicanti potrebbe rivelarsi catastrofica.

Disastri associati ai computer. Potrebbero iniziare loro una guerra nucleare non voluta. Oppure potrebbe collassare una rete diventata vitale per la nostra esistenza. Senza dire dei disastri voluti da pazzi e criminali.

Altri disastri tecnologici associati con l’agricoltura. L’agricoltura moderna è “pericolosamente” dipendente da pesticidi e fertilizzanti chimici.

Produzione del Bing Bang in laboratorio. Potrebbe sfuggire dal controllo degli scienziati.

Produzione di materiali pericolosi…

… Edward Farhi and Robert Jaffe suggested that physicists might produce ‘strange-quark matter’ of a kind which attracted ordinary matter, changing it into more of itself until the entire Earth had been converted (‘eaten’)…

Annientamento da extraterrestri. Il “grande silenzio” di Enrico Fermi fa prevedere vite aliene nascoste e quindi ostili.

Ci sono anche dei rischi di natura filosofica.

Pericolo delle religioni. I politici potrebbero convincersi che “non c’è niente da fare” per salvare l’umanità. Oppure che “Dio è con loro” e quindi possono permettersi di fare tutto.

Pessimismo alla Schopenhauer. Per alcuni la terra sarebbe un posto migliore se disabitata.

Relativismo etico. Nega che ci sia qualcosa per cui valga la pena battersi. Per il relativista: bruciare una persona viva per divertimento è sbagliato solo nell’ambito di certi codici morali.

Emotivismo etico. Per l’emotivista, bruciare viva una persona non è sbagliato, molto semplicemente genera disgusto in chi ha internalizzato alcuni codici.

Utilitarismo negativo. Per l’utilitarista negativo contano solo gli ultimi…

… Now, there will be at least one miserable person per century, virtually inevitably, if the human race continues. It could seem noble to declare that such a person’s sufferings ‘shouldn’t be used to buy happiness for others’—and to draw the conclusion that the moral thing would be to stop producing children…

Trascurare tutti gli altri puo’ essere molto pericoloso.

“Viventismo”. Per alcuni filosofi i “non nati” (non concepiti) non hanno peso, quindi l’estinzione non è di per sé qualcosa da evitare.

Filosofia dei diritti. Per alcuni filosofi esistono diritti intoccabili (o “non negoziabili”)… anche se il mondo dovesse collassare non siamo autorizzati a violarli.

In tanti minimizzano i danni arrecati dall’estinzione dell’uomo: altri esseri viventi ci rimpiazzeranno.

Ma noi non abbiamo idea di quanto sia frequente la vita nel cosmo, figuriamoci l’intelligenza!…

… It can seem unlikely that our galaxy already contains many technological civilizations, for, as Enrico Fermi noted… it could well be that in a few million years the human race will have colonized the entire galaxy, if it survives…

***

Torniamo ora a AA. Cosa dice, in breve?…

… we could hardly expect to be among the very earliest—among the first 0.01…

AA ci chiede di concentrarci su di noi e di partire da lì. In questo presenta una parentela con il principio antropico (PA)…

… The principle reminds us that observers, for instance humans, can find themselves only at places and times where intelligent life is possible…

PA ci fa notare come alcune cose siano eccezionali, ed altre molto comuni.

Per esempio, il fatto di esistere è qualcosa di eccezionale poiché l’universo che rende possibile la vita intelligente (ovvero noi) è un evento di per sé rarissimo. Quindi: o esistono molti universi e il nostro è uno dei tanti, oppure siamo stati fortunatissimi. E’ chiaro che di fronte ad un caso tanto straordinario l’ipotesi teista diventa vincente.

Ma, allo stesso tempo, PA ci dice anche che siamo esseri molto comuni. Leggete questo scambio di battute…

… In the New York Times, July 27, 1993, Gott reacts to some pointlessly aggressive criticisms by Eric Lerner. Lerner had held that he himself, for example, couldn’t usefully be treated as random. ‘This is surprising’, Gott comments, ‘since my paper had made a number of predictions that, when applied to him, all turned out to be correct, namely that it was likely that he was (1) in the middle 95 percent of the phone book; (2) not born on Jan. 1; (3) born in a country with a population larger than 6.3 million, and most important (4) not born among the last 2.5 percent of all human beings who will ever live (this is true because of the number of people already born since his birth). Mr. Lerner may be more random than he thinks.’…

Il nostro universo è un caso rarissimo ma noi – in quanto uomini tra molti uomini – siamo piuttosto comuni.

AA in fondo è un’estensione di PA nel momento in cui mette in luce il nostro essere “normali”…

… Carter suggests, no observer should at all expect to find that he or she or it had come into existence very exceptionally early in the history of his, her or its species. It is this simple point which led first him and then Gott to the doomsday argument…

Ciascuno di noi è unico per molti versi, ma per molti altri non c’è affatto alcuna ragione di ritenerci straordinari. Perché mai, per esempio, dovrei ritenermi straordinario riguardo all’ordine di nascita?…

… Carter suggests, no observer should at all expect to find that he or she or it had come into existence very exceptionally early in the history of his, her or its species. It is this simple point which led first him and then Gott to the doomsday argument…

***

AA è certamente controverso. Forse l’obiezione “indeterminista” è la più fondata…

… Suppose that the cosmos is radically indeterministic, perhaps for reasons of quantum physics. Suppose also that the indeterminism is likely to influence how long the human race will survive. There then isn’t yet any relevant firm fact, ‘out there in the world’ and in theory predictable by anybody who knew enough about the present arrangement of the world’s particles, concerning how long it will survive… Yet in order to run really smoothly, the doomsday argument does need the existence of a firm fact of this kind, I believe…

Come prevedere la dinamica di un universo radicalmente indeterminato?

Ma l’obiezione ha una risposta…

… For anyone who believes in radically indeterministic factors yet says that something ‘will very probably occur’ must mean that even those factors are unlikely to prevent its occurrence…

L’indeterminazione che noi conosciamo non è “radicale”, consente di fare previsioni.

C’è un’altra obiezione molto seria. AA è un argomento probabilistico. Il ragionamento probabilistico richiede classi ben definite, es: palline rosse, palline verdi, testa, croce, moneta ecc. Ecco, ma la classe “uomini vissuti sulla terra” è ben definita? Comprende sia uomini veri e propri (morti e vivi), sia uomini che devono ancora nascere. Ma un “uomo che deve ancora nascere” cos’è? Un uomo? Uno spirito? Un niente? Un nonsense? Una roba del genere, dice l’obbiettore, non puo’ formare una classe omogenea con gli altri uomini!…

… Any people of a heavily populated far future are not alive yet. Hence we certainly cannot find ourselves among them, in the way that we could find ourselves in some heavily populated city rather than in a tiny village…

A questa obiezione decisiva non si puo’ rispondere. O meglio, si puo’ rispondere raccontando storie che tutti noi comprendiamo perfettamente e in cui si parla in modo più o meno diretto della classe incriminata, quella degli “uomini che devono ancora nascere”. L’esistenza di queste storie dimostra di per sé che il concetto é sensato e utilizzabile. Ecco la storia dello smeraldo…

… Imagine an experiment planned as follows. At some point in time, three humans would each be given an emerald. Several centuries afterwards, when a completely different set of humans was alive, five thousand humans would again each be given an emerald. Imagine next that you have yourself been given an emerald in the experiment. You have no knowledge, however, of whether your century is the earlier century in which just three people were to be in this situation, or the later century in which five thousand were to be in it. Do you say to yourself that if yours were the earlier century then the five thousand people wouldn’t be alive yet, and that therefore you’d have no chance of being among them? On this basis, do you conclude that you might just as well bet that you lived in the earlier century?…

D’altronde, quando tutti noi parliamo di “generazioni future” facciamo riferimento ad un nonsense? Non credo.

***

L’ AA è semplicissimo…

… We should tend to distrust any theory which made us into very exceptionally early humans.’…

Il difficile è difenderlo dalle obiezioni.

Ecco una serie di errori in cui cade l’obiettore frettoloso.

Primo…

… Don’t object that your genes must surely be of a sort found only near the year 2000, and that in consequence you could exist only thereabouts…

Significherebbe non aver afferrato l’argomento…

… what Carter is asking is how likely a human observer would be to find himself or herself near the year 2000 and hence with genes typical of that period….

Poi c’è la solita obiezione: chi vince la lotteria dirà sempre che è stato straordinariamente fortunato, ma noi sappiamo che qualcuno vincerà sempre la lotteria, quindi questa enfasi sul caso è fuori luogo.

Le cose non stanno proprio in questi termini nel nostro caso. Facciamo un’ analogia più pertinente e capiremo subito la differenza…

… The doomsday argument is about probabilities. Suppose you know that your name is in a lottery urn, but not how many other names the urn contains. You estimate, however, that there’s a half chance that it contains a thousand names, and a half chance of its containing only ten. Your name then appears among the first three drawn from the urn. Don’t you have rather strong grounds for revising your estimate? Shouldn’t you now think it very improbable that there are another 997 names waiting to be drawn?… don’t be much impressed by the point that every lottery must be won by somebody or other….

Ecco un altro esempio per rispondere a chi dice “ogni lotteria deve pur essere vinta da qualcuno”…

… Suppose you see a hand of thirteen spades in a game with million-dollar stakes. Would you just say to yourself that thirteen spades was no more unlikely than any other hand of thirteen cards, and that any actual hand has always to be some hand or other? Mightn’t you much prefer to believe that there had been some cheating, if you’d started off by thinking that cheating was 50 per cent probable? Wouldn’t you prefer to believe it, even if you’d started off by thinking that its probability was only five per cent?…

Altro errore da evitare: descrivere AA come un argomento teorico…

… Don’t describe the doomsday argument as an attempt ‘to predict, from an armchair, that the humans of the future will be only about as numerous as those who have already been born’… The argument doesn’t deny that we might have excellent reasons for thinking that the human race would have an extremely long future…

Obiezione illusoria: se l’uomo primitivo avesse valorizzato AA si sarebbe sbagliato…

… Don’t object that any Stone Age man, if using Carter’s reasoning, would have been led to the erroneous conclusion that the human race would end shortly…

Il fatto che valorizzando AA ci si possa sbagliare non dice nulla sulla bontà di AA, visto che AA è un argomento probabilistico…

… it wouldn’t be a defect in probabilistic reasoning if it encouraged an erroneous conclusion…

Morale: AA aiuta nel pesare le evidenze empiriche. E’ un metodo da adottare nella pratica, non un argomento teorico.

L’errore delle “due razze”…

… Don’t object that if the universe contained two human races, the one immensely long-lasting and galaxy-colonizing, and the other short-lasting, and if these had exactly the same population figures until, say, AD 2150, then finding yourself around AD 2000 could give you no clue as to which human race you were in…

Risposta…

… a human could greatly expect to be after AD 2150 in the long-lasting race—which you and I aren’t… there would be nothing automatically improbable in being in a short-lasting human race…

Altro errore: scavalcare Bayes…

… Don’t protest that we can make nothing but entirely arbitrary guesses about the probabilities of various figures for total human population, i.e. the number of all humans who will ever have been born…

Bayes ci dice che noi abbiamo credenze che aggiorniamo in base alle evidenze. AA è conforme a questa intuizione: la credenza di base viene aggiornata ma continua a pesare nelle conclusioni…

… the doomsday argument, like any other argument about risks, can also take account of new evidence of efforts to reduce risks. Because it doesn’t generate risk-estimates just by itself, disregarding all actual experience, it is no message of despair…

Per comprendere meglio AA facciamo un ultimo esempio: se un test medico ha un falso positivo del 5% e voi risultate positivi, quale sarà la probabilità di essere malati? Per molti (chiamiamoli “frequentisti”) la risposta è semplice: 95%

Altri (bayesiani), prima di rispondere considerano anche la percentuale di malati nella popolazione. Se la percentuale è dell’ 1%, la vostra possibilità di essere malati è solo del 10%.

Siamo passati dal 95% (sbagliato) al 10% (corretto)! Capita la differenza tra “aggiornare” e “calcolare”? L’uomo razionale aggiorna, l’uomo-macchina calcola.

Ebbene, AA ci fornisce una base da “aggiornare”, il punto di partenza dell’ignorante, senza questa base le nostre conclusioni potrebbero essere molto diverse.

venerdì 10 febbraio 2017

The End of the World: The Science and Ethics of Human Extinction by John Leslie

The End of the World: The Science and Ethics of Human Extinction by John Leslie

You have 156 highlighted passages

You have 71 notes

Last annotated on February 10, 2017

The Introduction will give the book’s main arguments, particularly a ‘doomsday argument’Read more at location 252

the doomsday argument could do little to tell us how long humankind will survive. What it might indicate, though, is that the likelihood of Doom Soon is greater than we would otherwise think.Read more at location 255

One of the doomed humans complains of his remarkable bad luck in being born so late. ‘There have been upward of fifteen thousand generations since the start of human history—yet here I am, in the one and only generation which will have no successors!’Read more at location 267

Suppose that many thousand intelligent races, all of about the same size, had been more or less bound to evolve in our universe. We couldn’t at all expect to be in the very earliest, could we? Very similarly, it can seem, you and I couldn’t at all expect to find ourselves among the very first of many hundred billion humans—or of the many trillions in a human race which colonized its galaxy. We couldn’t at all expect to be in the first 0.1 per cent, let alone the first 0.001 per cent, of all humans who would ever have observed their positions in time.Read more at location 271

The doomsday argument aims to show that we ought to feel some reluctance to accept any theory which made us very exceptionally early among all humans who would ever have been born.Read more at location 281

Carter’s doomsday argument doesn’t generate any risk-estimates just by itself.Read more at location 287

It is an argument for revising the estimates which we generate when we consider various possible dangers.Read more at location 287

even if the ‘total risk’ (obtained by combining the individual risks) appeared to be fairly small, Carter’s doomsday argument could suggest that it should be re-evaluated as large.Read more at location 293

Hundreds of new chemicals enter the environment each year. Their effects are often hard to predict.Read more at location 312

Who would have thought that the insecticide DDT would need to be bannedRead more at location 312

They can now spread world wide very quickly, thanks to air travel.Read more at location 317

The death of the dinosaurs was very probably caused by an asteroid.Read more at location 322

You may be far more likely to be killed by a continent-destroying impact than to win a major lottery:Read more at location 322

An extreme ice age due to passage through an interstellar cloud?Read more at location 325

Earth’s biosphere: its air, its soil, its water and its living things interact in highly intricate ways.Read more at location 331

foolish to think we had foreseen all possible natural disasters.Read more at location 334

a genetically engineered organism reproduces itself with immense efficiency, smothering everything?Read more at location 338

breakdown of a computer network which had become vital to humanity’s day-to-day survival.Read more at location 350

deliberate planning by scientists who viewed the life and intelligence of advanced computers as superior—possiblyRead more at location 353

Some other disaster in a branch of technology, perhaps just agricultural, which had become crucial to human survival.Read more at location 358

Modern agriculture is dangerously dependent on polluting fertilizers and pesticides,Read more at location 359

the compression would indeed have to be tremendous, and a Bang engineered in this fashion would very probably expand into a space of its own.Read more at location 365

The possibility of producing an all-destroying phase transition,Read more at location 366

Edward Farhi and Robert Jaffe suggested that physicists might produce ‘strange-quark matter’ of a kind which attracted ordinary matter, changing it into more of itself until the entire Earth had been converted (‘eaten’).Read more at location 367

several scientists have suggested that everyone is listening and nobody broadcasting, for fear of attracting hostile attention.Read more at location 381

politician convinced that, no matter what anyone did, the world would end soon with a Day of Judgement.Read more at location 393

just as bad to choose somebody who felt that God would keep the world safe for us for ever,Read more at location 394

My Value and Existence was a lengthy defence of a neoplatonic picture of God as an abstract creative force,Read more at location 396

Schopenhauer, who wrote that it would have been better if our planet had remained like the moon, a lifeless mass.Read more at location 404

Ethical relativism, emotivism, prescriptivism and other doctrinesRead more at location 405

Relativism maintains that, for example, burning people alive for fun is only bad relative to particular moral codes,Read more at location 407

Emotivism holds that to call burning people ‘really bad’ describes no fact about the practice of people-burning. Instead, it merely expresses real disgust,Read more at location 409

feeling of duty not to burn people results from ‘internalizing’ a system of socially prescribed rules.Read more at location 411

is concerned mainly or entirely with reducing evils rather than with maximizing goods.Read more at location 426

Now, there will be at least one miserable person per century, virtually inevitably, if the human race continues. It could seem noble to declare that such a person’s sufferings ‘shouldn’t be used to buy happiness for others’—and to draw the conclusion that the moral thing would be to stop producing children.Read more at location 427

Some philosophers attach ethical weight only to people who are already aliveRead more at location 430

Some philosophers speak of ‘inalienable rights’ which must always be respected, though this makes the heavens fallRead more at location 434

advantages of uncooperative behaviour should always dominate the reasoning of anyone who had no inclination to be self-sacrificing.Read more at location 439

annihilation of all life on Earth would be no great tragedy. Other intelligent beings would soon evolveRead more at location 442

this overlooks the fact that we have precious little idea of how often intelligent life could be expectedRead more at location 443

It can seem unlikely that our galaxy already contains many technological civilizations, for, as Enrico Fermi noted,Read more at location 445

it could well be that in a few million years the human race will have colonized the entire galaxy, if it survives.Read more at location 447

we could hardly expect to be among the very earliest—among the first 0.01Read more at location 454

Now, suppose that you suddenly noticed all this. You should then be more inclined than before to forecast humankind’s imminent extinction.Read more at location 457

Carter’s reasoning provides us with additional groundsRead more at location 461

DOOMSDAY AND THE ANTHROPIC PRINCIPLERead more at location 462

The principle reminds us that observers, for instance humans, can find themselves only at places and times where intelligent life is possible.Read more at location 463

help to persuade us that our position in space and in time is in fact unusual:Read more at location 468

There would be nowhere else where we could possibly find ourselves.Read more at location 481

the anthropic principle can at the same time discourage the belief that it is more rare and unusual than is neededRead more at location 482

In the New York Times, July 27, 1993, Gott reacts to some pointlessly aggressive criticisms by Eric Lerner. Lerner had held that he himself, for example, couldn’t usefully be treated as random. ‘This is surprising’, Gott comments, ‘since my paper had made a number of predictions that, when applied to him, all turned out to be correct, namely that it was likely that he was (1) in the middle 95 percent of the phone book; (2) not born on Jan. 1; (3) born in a country with a population larger than 6.3 million, and most important (4) not born among the last 2.5 percent of all human beings who will ever live (this is true because of the number of people already born since his birth). Mr. Lerner may be more random than he thinks.’Read more at location 494

Carter suggests, no observer should at all expect to find that he or she or it had come into existence very exceptionally early in the history of his, her or its species. It is this simple point which led first him and then Gott to the doomsday argument.Read more at location 512

while everyone is inevitably unusual in many ways, that can be a poor excuse for looking on ourselves as highly extraordinaryRead more at location 517

Suppose that the cosmos is radically indeterministic, perhaps for reasons of quantum physics. Suppose also that the indeterminism is likely to influence how long the human race will survive. There then isn’t yet any relevant firm fact, ‘out there in the world’ and in theory predictable by anybody who knew enough about the present arrangement of the world’s particles, concerning how long it will survive—likeRead more at location 525

Yet in order to run really smoothly, the doomsday argument does need the existence of a firm fact of this kind, I believe.Read more at location 530

For anyone who believes in radically indeterministic factors yet says that something ‘will very probably occur’ must mean that even those factors are unlikely to prevent its occurrence.Read more at location 532

doomsday argument has now been thought about rather hard by some rather good brains.Read more at location 536

If it did, then almost all ‘anthropic’ reasoning—reasoning which draws attention to when and where an observer could at all expect to be—would be in severe trouble.Read more at location 538

Users of the anthropic principle therefore ask about an observer’s probable location in space and in time.Read more at location 540

Any people of a heavily populated far future are not alive yet. Hence we certainly cannot find ourselves among them, in the way that we could find ourselves in some heavily populated city rather than in a tiny village.Read more at location 545

Note: x OBIEZIONE SULLA CLASSE DI RIFERIMENTO. NN SI PUÒ PARLARE DI UOMINI CONSIDERANDO ANCHE CHI DEVE ANCORA ESISTERE. Edit

Imagine an experiment planned as follows. At some point in time, three humans would each be given an emerald. Several centuries afterwards, when a completely different set of humans was alive, five thousand humans would again each be given an emerald. Imagine next that you have yourself been given an emerald in the experiment. You have no knowledge, however, of whether your century is the earlier century in which just three people were to be in this situation, or the later century in which five thousand were to be in it. Do you say to yourself that if yours were the earlier century then the five thousand people wouldn’t be alive yet, and that therefore you’d have no chance of being among them? On this basis, do you conclude that you might just as well bet that you lived in the earlier century?Read more at location 556

We should tend to distrust any theory which made us into very exceptionally early humans.’Read more at location 569

Here, then, is a quick introduction to various common objections,Read more at location 573

(a) Don’t object that your genes must surely be of a sort found only near the year 2000, and that in consequence you could exist only thereabouts.Read more at location 574

what Carter is asking is how likely a human observer would be to find himself or herself near the year 2000 and hence with genes typical of that period.Read more at location 575

(b) The doomsday argument is about probabilities. Suppose you know that your name is in a lottery urn, but not how many other names the urn contains. You estimate, however, that there’s a half chance that it contains a thousand names, and a half chance of its containing only ten. Your name then appears among the first three drawn from the urn. Don’t you have rather strong grounds for revising your estimate? Shouldn’t you now think it very improbable that there are another 997 names waiting to be drawn?Read more at location 583

Don’t protest that your time of birth wasn’t decided with the help of an urn.Read more at location 587

Again, don’t be much impressed by the point that every lottery must be won by somebody or other.Read more at location 589

Suppose you see a hand of thirteen spades in a game with million-dollar stakes. Would you just say to yourself that thirteen spades was no more unlikely than any other hand of thirteen cards, and that any actual hand has always to be some hand or other? Mightn’t you much prefer to believe that there had been some cheating, if you’d started off by thinking that cheating was 50 per cent probable? Wouldn’t you prefer to believe it, even if you’d started off by thinking that its probability was only five per cent?Read more at location 590

(c) Don’t describe the doomsday argument as an attempt ‘to predict, from an armchair, that the humans of the future will be only about as numerous as those who have already been born’.Read more at location 593

The argument doesn’t deny that we might have excellent reasons for thinking that the human race would have an extremely long future,Read more at location 595

(If you begin by being virtually certain that an urn with your name in it contains a thousand names in total, and not just ten names, then you may remain fairly strongly convinced of it even after your name has appeared among the first three drawn from the urn. Still, you should be somewhat less convinced than you were before.)Read more at location 596

(d) Don’t object that any Stone Age man, if using Carter’s reasoning, would have been led to the erroneous conclusion that the human race would end shortly.Read more at location 598

it wouldn’t be a defect in probabilistic reasoning if it encouraged an erroneous conclusionRead more at location 601

(e) Don’t object that if the universe contained two human races, the one immensely long-lasting and galaxy-colonizing, and the other short-lasting, and if these had exactly the same population figures until, say, AD 2150, then finding yourself around AD 2000 could give you no clue as to which human race you were in.Read more at location 608

a human could greatly expect to be after AD 2150 in the long-lasting race—which you and I aren’t.Read more at location 611

there would be nothing automatically improbable in being in a short-lasting human race.Read more at location 614

(g) Don’t protest that we can make nothing but entirely arbitrary guesses about the probabilities of various figures for total human population, i.e. the number of all humans who will ever have been born.Read more at location 616

the doomsday argument, like any other argument about risks, can also take account of new evidence of efforts to reduce risks. Because it doesn’t generate risk-estimates just by itself, disregarding all actual experience, it is no message of despair.Read more at location 621

Iscriviti a:

Commenti (Atom)